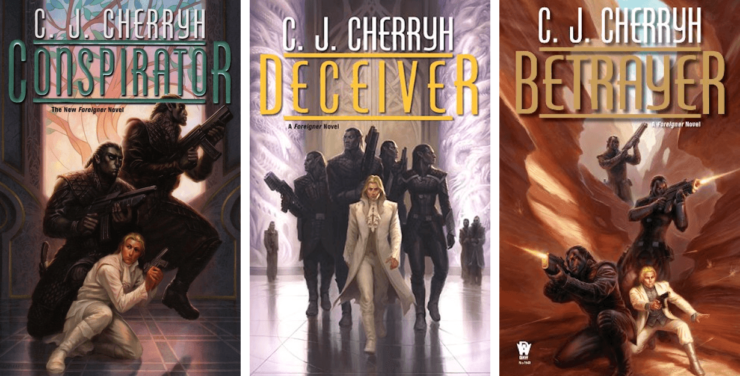

Like the previous trilogy in Cherryh’s Foreigner series (discussed here), the fourth trilogy (Conspirator, Deceiver, Betrayer) is also heavily focused on politics, notably the aftermath of the coup against Tabini, but all Bren really wants is to go fishing on his boat and not do politics.

So, naturally, he quickly gets dragged into some *extremely messy* politics!

It starts at the end of winter after Tabini’s return to power, so somewhat less than a year later than the events in the previous books. Once again, this trilogy takes place over the course of about a week, a feat of narrative skill that I hope someday to be able to emulate.

At the beginning of the books, Bren is considering the arguments he will make against the use of wireless communication (i.e. cell phones) among the atevi, which he will then present at the legislative session next month. Because a group of people has claimed his apartment as theirs for historical/familial connections, he decides to ask Tabini if he can go to his estate on the coast and prepare his arguments and relax. Tabini grants permission, and off he goes.

The reasons Bren puts forward against cell phones revolve around the traditional lines of communication for atevi. Lords don’t contact other lords; their bodyguards and other staff talk to each other and present a solution or propose a meeting, etc. This roundabout mode of communication allows talk to proceed along lines of man’chi and association and preserves clan authority. If people can just call each other, the heart of atevi culture—clan authority and man’chi—will be dangerously weakened. This is something Tabini recognizes at the end of the last trilogy when Bren describes the instant messaging functions that the ship had, and he—unusually for Tabini, who is keen on gadgets and technology—doesn’t think it should be allowed.

So, back to Bren’s estate. He’s invited his brother to visit for a fishing trip, and even though Toby and (Bren’s ex, and Toby’s current girlfriend) Barb have interacted with atevi many times, Bren still has to explain to them that human manners are not the same as atevi manners. Barb horrifies Bren’s staff by clinging to Toby as they come to dinner, among other issues that occur over the time they’re there. Bren notes, narratively, that this is the same sort of misunderstanding that led to the war: humans thought atevi would adapt and become more friendly; atevi thought humans would learn civilized behavior. Which, of course, didn’t happen.

Buy the Book

Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters

In Betrayer, Bren negotiates with Machigi as a neutral party, and because he has to propose things to Machigi and show that he is representing his interests, not Tabini’s, he calls Machigi “aiji-ma,” which is a term that shows personal loyalty and respect. He has never used the term outside of Tabini or Ilisidi, but he uses it here consciously and deliberately, even though it could potentially give his staff, notably his bodyguards, conflicts of man’chi, because his man’chi directs theirs. When he discusses this with them shortly after the conversation, his bodyguard assures him that they have no issues. It isn’t explained why this is the case, but Bren accepts it.

One thing I haven’t really discussed thus far is how the Assassins’ Guild uses hand signs and coded speech to communicate. We get very few examples of specific signs or codes, only Bren’s comments that they’re being used. Here, after this discussion, we do get a precise description: five fingers held up symbolizes the aishid-lord unit. Another one described is the thumb drawn across the fingertips, which means different things in different situations, but generally connotes elimination or erasure.

Cajeiri’s POV returns here as well. He sneaks out of the Bujavid with his two Taibeni guards and follows Bren to his estate. This naturally causes disruption and shakes loose a whole lot of political fallout from the long-standing conflict between Tabini and the southern association, of which Machigi is the nominal head. (They were behind Murini’s coup.) We get both a deeper view of man’chi from the atevi side and a lot of negotiation of language and communicative boundaries as Cajeiri seeks to talk with Toby, both of which are extremely interesting narratively and in the arena of linguistic worldbuilding.

The atevi feelings that Cajeiri’s elders were concerned about in the previous set begin to come in, as Ilisidi expected they would, even as he thinks in ship-speak when he’s upset so he can think things no one else can. He struggles internally to maintain a hold on the things he learned on the ship and the associations he formed there: he doesn’t want to forget them. He sees the ship kids as valuable associates for the future—which is in line with what we learn about man’chi from an aiji’s perspective over the course of this trilogy. Bren is somewhere between kidnapped and held hostage at Machigi’s, and Cajeiri is viscerally angry about this, because Bren is his: his ally, his associate, his responsibility. Aijiin and lords, toward whom man’chi flows, have a responsibility to the people below them. They remember people’s service for generations and repay favors. This reminds me of the way Tiffany Aching in Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men views selfishness: “Make all things yours! … Protect them! Save them! … How dare you try to take these things, because they are mine!”

While Bren is off at Machigi’s and a war is about to break out around Bren’s estate, Cajeiri has the responsibility to translate for Toby and Barb, who can’t understand much Ragi. He runs into difficulty when he gets into the nitty gritty of politics, because he never had any reason to talk about that in ship-speak with his human associates. So he has to paraphrase and simplify the complex and complicated political situation that Ilisidi explained to him into the ship-speak he knows. He doesn’t know any words for distances, for example, because the ship only had fore and aft, so he has to be vague about how far away things are.

Cherryh uses a few signs in Cajeiri’s ship-speak to signal that his handle on the language isn’t perfect but is good enough to manage. He doesn’t use the past tense: he tells Toby that Banichi and Jago “go with” Bren. He also doesn’t use the subjunctive (hypotheticals). I didn’t make a note of the specific example, but it’s in Ch. 15 of Betrayer—instead of “Bren would go” for example, he would say “Maybe Bren goes.”

Cajeiri also encounters a cross-cultural issue, when he has to figure out how to refer to Toby when addressing him. He ends up going with “nand’ Toby,” a mixed-code phrase, because using no title, like the humans do, didn’t feel right, and ship-speak sir was too broad. Apparently no one ever taught him “mister” or “ms,” which makes sense, because he’s never been around humans who call each other “Mr. Smith” or what-have-you. Bren calls his brother simply by his first name. He calls the president by his first name, because they’re old friends. Presumably Cajeiri’s ship associates had a way to address their parents and their friends’ parents, but it wasn’t other than sir or ma’am.

While it’s never said outright, Mosphei’ (and ship) are presumably descendants of English speakers. Various cultural markers are very US American (overfriendliness, lack of formal titles and formality), and most of the names have an Anglo background, though there are some nods to people with other ethnic backgrounds (Ramirez, Ogun).

We have another set of books where the POV characters negotiate a cross-cultural landscape, and we get to see even more of what’s going on inside Cajeiri’s 8-year-old head. He likes to use human idioms, commenting on his favorites with “as Gene (or Bren) would say.” For example, “Hell, nand’ Bren would say. Bloody hell.”

Do you have any favorite Cajeiri-isms, atevi proverbs, atevi translations of human proverbs, or the like? Or atevi words that could be easily mispronounced as different words?

CD Covington has masters degrees in German and Linguistics, likes science fiction and roller derby, and misses having a cat. She is a graduate of Viable Paradise 17 and has published short stories in anthologies, most recently the story “Debridement” in Survivor, edited by Mary Anne Mohanraj and J.J. Pionke. You can find her current project, a book on practical linguistics for writers, on Patreon.